In 2009, the Van Gogh Museum and the Huygens Institute published a new edition of the correspondence of Vincent van Gogh, both online and in print. This article discusses how the online edition dealt with the richness of material (using the strategies of flexibility and user control, powerful search and filter facilities and indexing and cross-referencing). It describes the technical infrastructure and the conversion that was needed from word processor documents into XML. It also examines the relation between the book and web versions of the edition. In conclusion, the article mentions some of the user reactions to the edition and briefly mentions some of the prospects for future scholarly editions.

1 Introduction

Besides his paintings, Vincent van Gogh left posterity an impressive corpus of letters. Most of the letters were sent to his brother and Maecenas Theo, but others are addressed to other family members or artists such as Bernard or Gauguin. The letters provide unique insight both into his development as an artist and into his frequently difficult personal life. They have inspired readers ever since their first publication.

Vincent van Gogh – The Letters is a new digital edition of this correspondence. The full scholarly edition is freely available online at www.vangoghletters.org.[2] The edition contains all extant letters (902) sent by or to Vincent van Gogh. For each letter, it provides a full facsimile, a transcription in the original language (Dutch or French), a new English translation and extensive commentary. Essays introduce readers to Van Gogh, his circle, the letters and their publication history. The edition was published by the Van Gogh Museum and the Huygens Institute in October 2009, after 15 years of preparatory research. [1] A slimmed-down book version was published in three languages (Dutch, French and English) and is targeted at sustained reading. [2]

In this article I discuss some features of the new edition: the way we coped with the abundance of material to be included in the edition, the technology employed in creating the edition, the relation between its web and book versions, the way the edition has been received and the prospects for future scholarly digital editions.

2 The embarrassment of riches

One of the main challenges in preparing this edition was the wealth of material to be included in the digital edition. The material consisted of more than 900 letters in several manifestations, accompanied by letter-level and edition-level commentary, 2000 illustrations of works of art discussed in the letters, and many internal references. Secondary material includes a timeline of Van Gogh’s life, maps of the areas where he lived, indexes, fragments of family correspondence that help elucidate Van Gogh’s letters, and a bibliography. How could we avoid our users getting lost in these riches? How to create an edition that allows intuitive navigation? We used three basic strategies to ease navigation of the site: fle-xibility and user control, powerful search, and cross-referenced indexes. In this section I will discuss each of these strategies.

2.1 Flexibility and user control

Users are expected to come to the site with differing perspectives, interests and linguistic capabilities. In order to accommodate these divergent interests, we have tried to create a user interface for the edition that provides different ways of exploring and viewing the letters – while maintaining consistency and clarity.

A simple example of this flexibility is that there are multiple ways of accessing the letters: selecting a letter by number, choosing from a list of all letters, or making a selection based on correspondent, sending place, or period in Van Gogh’s life. As we expect that many visitors will be especially drawn to the sketches Van Gogh often included in or with his letters, there is a separate menu option that displays all letters with sketches. The menu bar that provides these options, along with access to the site’s other facilities, is a permanent fixture on all screens of the site.

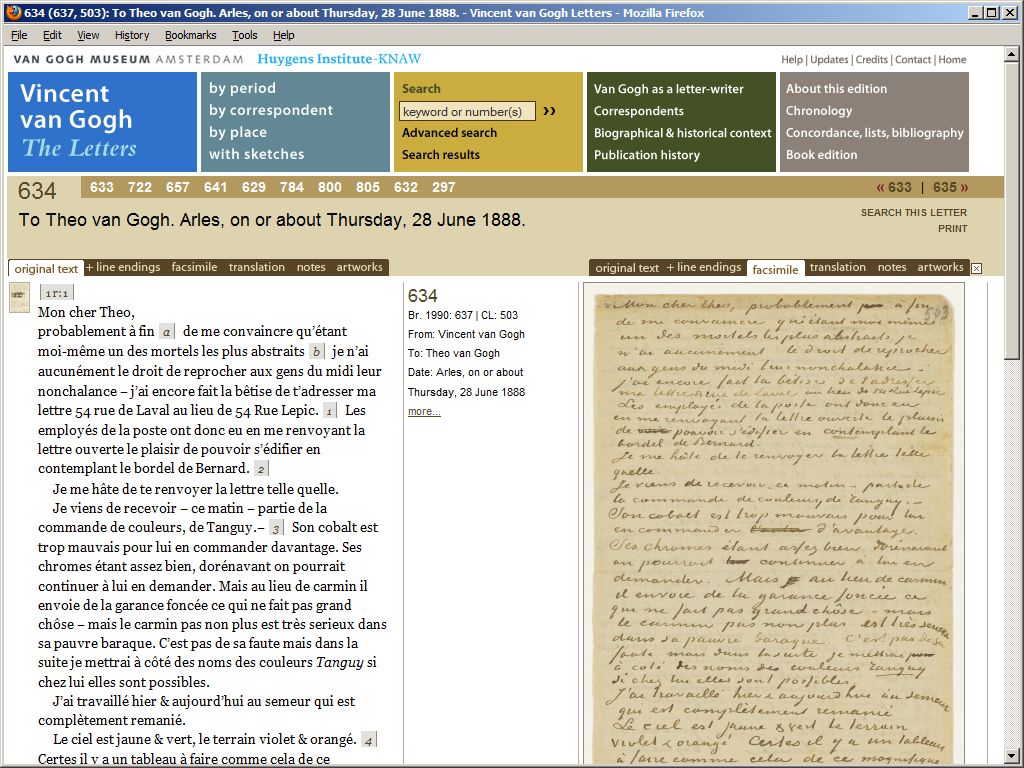

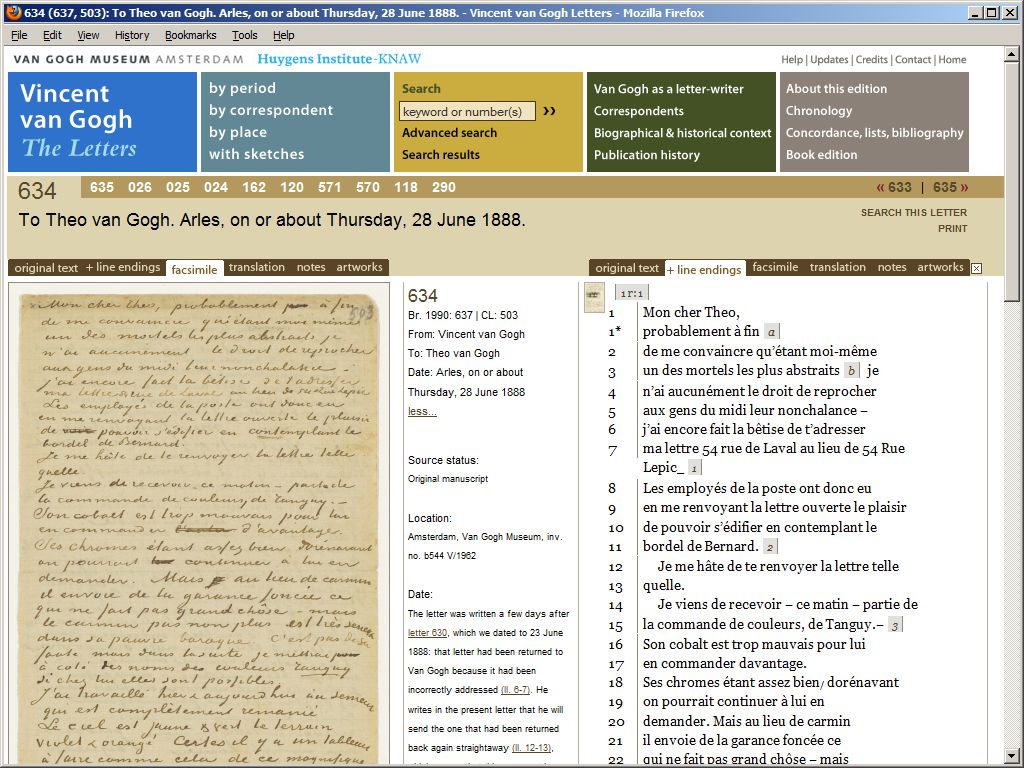

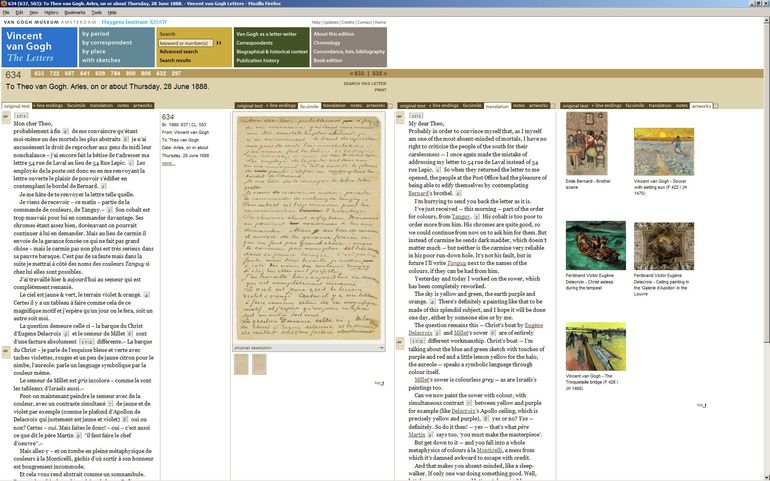

Another example of ›user control‹ is the way the site displays a letter’s several manifestations. The basic layout of the screen is shown in Figure 1. The letter is displayed in two columns, and the user can select which manifestation he or she wants to see in these columns: original text, artworks, translation, facsimile, or notes. For those that want to read the facsimile there is a version of the transcription matching Van Gogh’s lines. The artworks column displays thumbnails of works of art mentioned in the letters. Letter-level comments (on dating, included sketches, ongoing topics) can optionally be displayed in the middle co-lumn separating the two letter columns (Figure 2). This column can also be used to display individual notes, freeing up the other columns for display of other manifestations. On sufficiently wide screens, the user can open two more columns (Figure 3). From the facsimile or the artwork columns, the user can zoom in on the facsimile or open a larger display of the work of art, shown on top of, but not hiding, the rest of the screen.

As a result, the user is free to view those constituents of a letter that are most relevant to his or her interests and background. When moving to another letter, apart from the facilities mentioned above, the user can also move to the next or previous letter, or access one of the letters hyperlinked from the current letter’s commentary and notes. As an aid in returning to previously viewed letters, the system maintains a list of the last ten letters seen by the user.

In a way, these are of course very basic facilities. Still, it is not that often that one encounters a site which actually offers these facilities in a reasonably elegant implementation.

2.2 Searching and filtering

Search facilities are essential to scholarly use of a digital edition, especially if the edition contains a substantial amount of text in multiple layers. The Van Gogh edition has three options for searching: simple, local and advanced.

A simple search box is integrated into the site menu (the same box can be used for selecting a letter by number). The results are sorted by date. When a letter is displayed, the content of that specific letter can be searched using the local search (The browser’s search facility is not sufficient, as not all of the letter’s content is displayed at the same time).

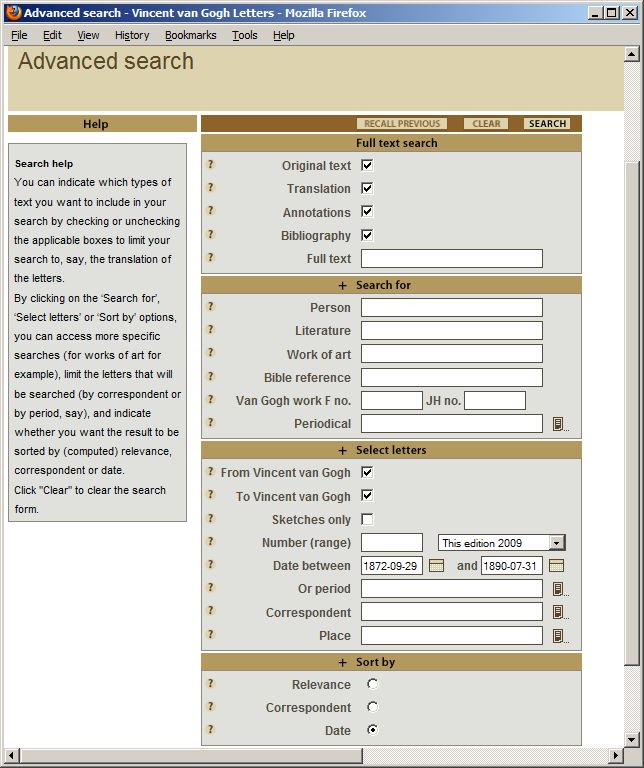

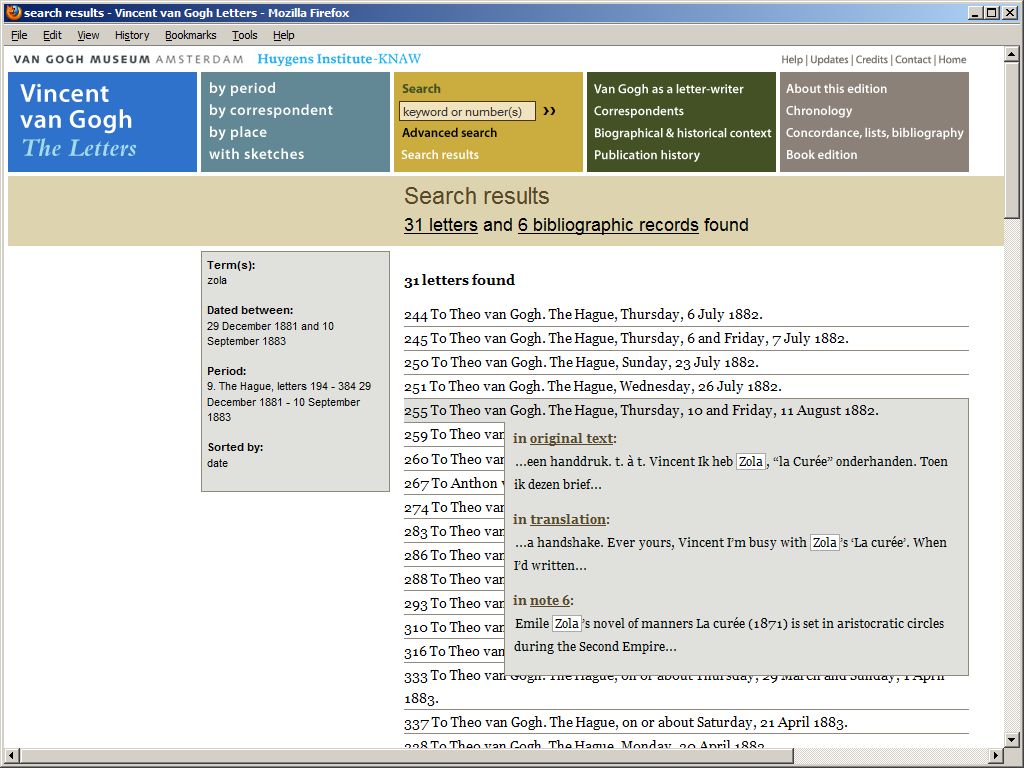

The advanced search facility (Figure 4) allows users to search in the text, optionally limiting their search to one or more layers (namely text, translation, annotation and bibliography). They can also search for references to persons, literature, works of art, the Bible, works of Van Gogh and magazines that Van Gogh read. If desired, the search can be limited to a filtered subset of the letters: letters from or to Van Gogh, letters exchanged with a certain correspondent, letters from a certain period, etc. By entering only the filter criteria and omitting the search criteria, the search facility can double as a selection facility, displaying for example only Theo’s letters to Vincent or the letters exchanged with his sister Willemien in the Arles period. Finally, the user can indicate how the letters are to be sorted. Search output consists of a list of letters. The search hits are displayed in context on a mouse-over (Figure 5). The most recent search results are always accessible through the site menu.

Searching is important, because it turns a site where one can wander around into a tool for daily work. Search facilities allow one to approach a site with a concrete question in mind which one can hope to get an answer to. As Jakob Nielsen says: »Search lets users control their own destiny«, and it is their »escape hatch when they are stuck« [3]. We have assumed that Nielsen’s advice to downplay the advanced search facility is less relevant to a site with a predominantly scholarly audience.

2.3 Index and cross-reference

References to persons, works of art and literature that Van Gogh mentions are accessible through the site’s search facility. Many digital editions rely on search alone to provide access to the texts’ references to persons and objects. Plain text search alone, however, cannot provide an overview of all (for example) persons mentioned in a work, and it cannot facilitate hyperlinks from references to those persons to other places where they are mentioned.

It was therefore decided to tag all references to persons, works of art, literature read by Van Gogh and Bible references. Based on the tagging, the site can provide an index of persons, works of art and literature that are mentioned on the site. Perhaps more importantly, the tagging facilitates cross-references from each of the places that mention (for example) a person to the other references to that person. The indexes are based on simple databases that hold elementary information about the persons and works mentioned (for example »Julien François Tanguy (père Tanguy) (1825-1894) seller of artists' materials in Paris«). This information pops up when the mouse is moved over the reference to person or work; and if you click the reference you get a list of the places where this particular work of art is mentioned.

Taken together, these facilities provide an overview of the persons and works mentioned in the correspondence or notes, and therefore also of those not mentioned (something else that search cannot provide), certainty about other references to person or work in literally a single click, and zero-click access to for example years of birth and death and nationality of mentioned artists.

3 Technology

Work on the edition started in 1994, well before the period of ubiquitous web access. The edition was originally conceived as a 12-volume book edition. It was only in 2004 that it was decided to publish the complete edition online. This created the need to transform the word processor files used by the editors in a format suitable to digital publication. This section will describe the edition’s technical infrastructure and the necessary conversion.

3.1 Edition infrastructure

Basis for the digital edition are XML files encoded according to theText Encoding Initiative’s Guidelines. In the current TEI version it is possible to create document schemas tailored to specific document collections. We created a schema definition for the Van Gogh letters which contains exactly those TEI elements and attributes we needed in order for the schema to be maximally effective in validation and guided editing. Some of the encoding was ›borrowed‹ from theDALF Project, the Flemish letter project. For each letter, a single file holds the letter’s metadata, references to the page images, the original text, translation and annotation. A number of supplementary TEI files hold edition-level commentary, the bibliography and some of the supporting material. Information about the works of art and information that supports searching is held in a number of database tables. The programs displaying all of this are written in Ruby. For searching, we use the Lucene search engine. [4]

3.2 Conversion

The conversion from word processor documents into this structured XML (TEI) format proved to be a complex procedure. The reasons for this were twofold: (1) apart from a (technical) format change, the conversion was used to enrich the documents with information only implicitly present in the word documents; and (2) the presentation-oriented internal structure of the word processor documents contained inconsistencies that only appeared when trying to convert them into a structured format.

As to (1), the data in the word processor documents included for example the letter’s number in the present edition, but also the numbers used in previous editions of the letters. The conversion process had to deduce these numbers from the document layout. A much more complicated example of enrichment during conversion is the fact that the letter transcription was line-by-line, and the paragraph structure had to be deduced from indentation, white lines, and use of extra spaces at the end of lines.

As to (2), the conversion process was made considerably more difficult by Microsoft Word’s many ways of (visually) achieving the same result. Paragraph indentation for example can result from starting the paragraph with a tab character or from the paragraph’s display properties. A numbered list can contain »hard« numbers or result from automatic numbering. A number of extra complications arose because of unexpected leftovers from an earlier conversion from WordPerfect into MS Word.

We decided to outsource the one-time conversion to external programmers, concentrating our own resources on development of the permanent web application. The conversion was accomplished by converting the Word 2000 documents into Word’s own XML format. A C++-application performed the conversion into TEI/XML.

We could check the conversion results using the elementary display facility for the letters we had already developed (this was available early on in the process because of the agile development methodology we employed). [5] Automated checking was done through XML schema validation and separately developed scripts. Still, the end result of conversion was nowhere near the quality we had hoped for. Extensive manual checking and correction proved necessary.

Thus, the conversion was not a painless process. Nonetheless, a manual conversion would have been much more expensive; it would have introduced countless ways of creating new, and less consistent, mistakes, and would have needed extensive checking, too.

4 Book and Web

One of the unique properties of this edition is that a free and complete web edition is accompanied by a commercially available and not inexpensive book which offers only part of the web edition’s contents. The Van Gogh edition is one out of a number of recent hybrid publications. [6] We did not expect the website’s existence to harm book sales, as book and web were designed with different audiences and use cases in mind. The website was conceived as the full scholarly edition, detailing the results of 15 years of research. The book edition was conceived as a reading edition serving the many people who love Van Gogh’s art and letters. Even though some of the publishers involved in the project were hesitant at first, the expectation for book and web to be complementary rather than competing products has come true.

It should be noted that it is not unprecedented for books to be freely available online and being for sale in print. Among others, the US National Academies Press, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, O’Reilly Books, and the science fiction authors collaborating in the Bean Free Library all give free online access to all or part of their publications. [7] For some, this may be motivated by ideological considerations about the desirability of open access to scholarly publication, or an institute’s mission to disseminate as widely as possible its research output. For others, such as author Cory Doctorow, the reasons are also commercial: the extra exposure gained outweighs a possible loss in sales. [8] The increasing popularity of e-reading devices may have an impact on some of these decisions, as sustained reading of an electronic text becomes a common practice. However, it is less likely to affect texts consulted for scholarly use. In the case of the Van Gogh edition, the limited screen size of most e-reading devices and the fact that they are black and white only [9] makes them unlikely to be successful competitors to the book edition.

The website offers searching, hyperlinking and zooming facilities the book environment obviously cannot offer. Apart from this, the main differences between web and book are that the website, unlike the book, offers a full facsimile of the letters and that the annotations and introductory material have been substantially reduced for the book. The book also misses a number of features that were expected to be of interest only to scholars: The text version with original line-endings and the physical description of the letters are missing from the book. On the other hand, an important difference between the web and the book versions is the books being mono-lingual. The book buyer buys an edition that is either in Dutch, in French or in English. Dutch or French-speaking readers who aren’t comfortable with English have a clear reason for buying the book.

However, even for native speakers of English, the books and the web have different use-cases. The books serve sustained reading and contain many beautiful illustrations to which a computer screen cannot do justice. The website is easily navigated, it can be searched, and one can jump from one letter to another without effort. The availability of the website in fact enhances the value and usefulness of the book: the book owner can use the website as a complementary tool to the book, using all the facilities that are unique to the web environment: searching, copy-and-pasting text into email, articles and weblogs, referring friends and colleagues to one’s discoveries using hyperlinks to the web edition, etc.

It is interesting to notice that the books to some extent have adapted to what readers in a digital age are beginning to take for granted: Each reference to a work of art is illustrated by a thumbnail image that refers to a fuller reproduction given the first time the work is mentioned. Other book features, too, anticipate its use as a hypertext. As an example, the outer margin on right-hand pages contains letter numbers, facilitating quick access to an individual letter; on the left-hand pages the outer margin shows the period as well as the place where Van Gogh lived in that period. Lists of ongoing topics refer the reader to letters where topics discussed in the present letter first came up.

On the other hand, there is also much on the website that is reminiscent of the book. To some extent it was the result of a conscious decision that the several products from the Van Gogh letter project (website, book, and also an exhibition) should have a similar »look and feel«. Among others, this includes the use of the colours (blue) and the fonts that were employed. However, when looking at the site menu (Figure 6), one can see that there are also other similarities. Reading the menu from left to right, we first encounter the table of contents for the letters (a full, sequential table of contents and several alternative orderings), then the search facility, then the explanatory and contextualising essays, and finally the indices and appendices. It is no coincidence that this matches the order of the equivalent elements of the book, the exception being the reference to the search facilities, which has no equivalent in the book. A distinction intrinsic to the difference between the media is that the books have to actually put the material – the table of contents, the letters, the essays and the back matter – in a predetermined physical sequence, whereas on a website this is a matter of presentation only, one view among many potential views. On the website, references to front and back matter appear with the search facility at the top of the window, visually reinforcing the »overview« function of the menu. Central in this is the search box, hovering over the creation like the eye of God.

This permanent availability of the apparatus for moving elsewhere may imply a propensity to »treacherous reading«, as it was called by Terje Hillesund in 2010. Hillesund has studied, among other things, the implications of the physicality of book and web. The very fact that the book volumes require heavy lifting while the website is handled by mouse click implies a different attitude in reading – less prone to ponder a single letter, more easily distracted, perhaps. The layout of the website assumes a reader or user who makes use of the site guided by his or her own interest of research questions. The book assumes a reader willing to let himself be guided by the interests of the text.

5 What comes after this?

The book edition of the letters has been reviewed very widely and very favorably. Unfortunately, as of yet we do not seem to have a tradition of reviewing websites, however much they may claim to be a serious literary and scholarly undertaking. Most of the book reviews mentioned the website only in passing, if at all.

This does not mean we are left in the dark about the public’s reaction to the site. First of all we have statistics about the number of people visiting the site. Since its launch, the average number of visits is about a thousand each day. Many of the site’s visitors have written on their own sites and weblogs about the merits of the edition: »an unbelievably wonderful online archive of all the letters, meticulously organized«,[3] »colossale enterprise, très bien référencé«,[4] »the way the website works is itself a work of art«,[5] »terrific online database, searchable and free for the using. It's quite an achievement too«,[6]»La navigation est très intuitive et les possibilités offertes sont tout ce que l'on peut demander. … Une superbe démonstration de ce qu'il est possible d'offrir au monde à travers le système Internet«.[7]All this is of course quite gratifying. Other people have mailed to the site’s contact address, expressing their appreciation. One reader wrote us »thanks for making such a marvelous gift.«

This is not meant to suggest that the edition we built is perfect – there are obvious flaws and limitations. [10] Still, for a classical edition, based on the model of the best printed editions, the Van Gogh website may get close to being as good as it can get.

In the previous section, we listed differences between book and web editions. At a more basic level, however, the similarities between the web and book version of the edition are very noticeable. The edition, book and web, results from a very classical editorial undertaking, in the sense that it is only published after being completed, it is a product of a small group of editors, there is no user involvement in the creation of the edition, nor can users add or enrich the material in any way. In many respects, the edition is a closed universe. The number of hyperlinks pointing to elsewhere on the web is limited. As an instrument for studying the letters, Van Gogh’s life and his art, the edition is, if we may believe the comments we receive, very useful. Viewed as a website, seen from the view point of what a website might be, it is also the expression of a paradigm that is somewhat at odds with current web trends and current editorial thinking.

Over the past few years, a number of scholars have called for editions that harness the power of the internet in ways unimaginable within a book context. Ray Siemens (2005) asked for digital editions that include text analysis tools, Peter Robinson (2003) called for other analytical tools and facilities for users to enrich the editions, Martin Mueller (2009) suggested digital editions be created in collaborative fashion, Cathy M. Hajo (2010) wants to engage the ›crowd‹ in helping to create the edition.

In these respects, the world of scholarly editing still has a long way to go. We’re beginning to see text analytical facilities in projects such as the Monk project, which is however not itself a scholarly edition, but rather an aggregation of scholarly material edited elsewhere. The possibilities of collaborative editing are explored in a host of projects (Terras 2010), such as the Huygens Institute’s edition of Bartholomaeus Anglicus’ medieval encyclopaedia and UCL’s Bentham Papers Transcription Initiative.

I have no doubt that we are going to see interesting experiments in digital editing over the coming years. The Huygens Institute intends to be at the forefront of these developments – developments that should in no way replace the in-depth engagement with the text and scholarly accuracy that, I believe, the Van Gogh edition demonstrates.

Acknowledgements

Editors of the Van Gogh site are Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten and Nienke Bakker. The site design is by Bureau Zeezeilen, notably Geert Henderickx and Alfred Marseille. Decisions about basic functionality and navigation were made jointly by the editors, the designers, Bas Doppen (Huygens Institute) and the author. Lead programmer of the site is Bram Buitendijk.

Fig. 1: Basic screen layout: letter displayed in multiple columns

Fig. 2: Middle columns showing a letter metadata

Fig. 3: Screen with four columns

Fig. 4: The advanced search facility

Fig. 5: Search hits

Fig. 6: Site menu